Phoebe dynevor pregnancy, will there be a second season of bridgerton on Netflix

In Regency England, how true is this racy tale of sex and scandal?

You've never seen a period piece like Bridgerton before, possibly.

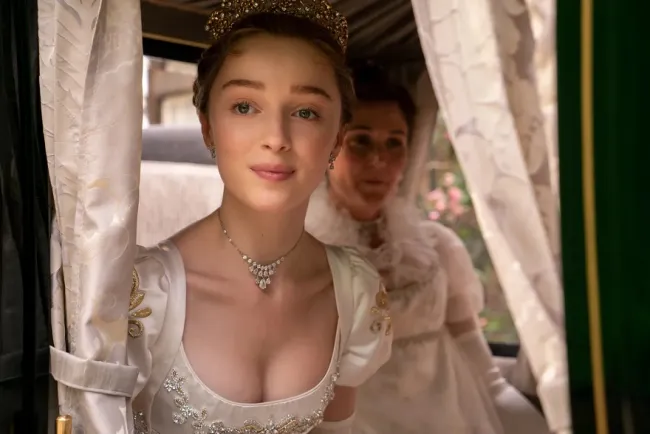

Set in London in 1813, the juicy drama follows beautiful young aristocrat Daphne Bridgerton (Phoebe Dynevor) from executive producer Shonda Rhimes as she makes her social debut with the intention of marrying for love. Bridgerton deliberately takes some license with history on the basis of the novels by Julia Quinn. Simon Basset, aka the Duke of Hastings (played by Rege-Jean Page), the romantic lead, is black, just as Queen Charlotte is.

When it comes to sex, Bridgerton goes there as well, which, of course, was part of daily life in Regency England.

"I was obsessed with the 1995 BBC Pride & Prejudice. Obviously, Colin Firth coming out of that lake with the white shirt is seared in my mind," says producer and showrunner Chris Van Dusen, a veteran of the Controversy Shondaland series, not exactly known for its restraint. "But I wanted to see a period piece that went further than that."

Daphne, who is unaware of the birds and bees on her wedding night, may seem naive to contemporary audiences, but Bridgerton adheres to a certain degree of social realism when it comes to courtship, marriage and sex, even if it gets much more explicit than Jane Austen ever did.

This season, I refer to it as "I refer to this season as 'the education of Daphne Bridgerton'," says Van Dusen. "She starts out as this young innocent debutante who knows very little of love. And she knows nothing of sex. And over the course of the series, we watch her transform entirely."

Here's a look at the realities in Regency England of sex, romance and scandal.

What has the market for marriage been?

Think of it as The Bachelorette's high-society version.

Each year, for the approximately six-month social season, a small group of aristocratic British families descended on London when balls, concerts, dinners and other lavish parties brought together eligible young men and women, says Bridgerton historical consultant Hannah Greig. The season began, as seen in the series, when young women from noble families were introduced to the real-life Queen Charlotte at the ball she first held in 1780 while standing next to a huge birthday cake. (With each sovereign, the tradition persisted until Queen Elizabeth II nixed the practice in 1958.)

Romance was in the air, but by controlling the pool of suitors, the real goal was to put together rich, powerful families and "keep the money and the power within a fairly small circle of society by controlling the pool of suitors," says Greig. Women like Daphne would have had some influence over who they danced with or publicly decided to court, but the selection of candidates was small, and maybe it would have been particularly suitable for just a few of the bachelors. She says, "That's what gives it the 'market' aspect,"

In order to establish the impression that they are a couple, Daphne and Simon walk the promenade together. Going public was a crucial step in the courtship process, with chaperones, of course. "People notice a couple together and it becomes taken as writ that they are engaged to be married," Greig says. "Marriage is not just a private contract, it's about presenting yourself in public."

For women, the obligation to secure a marriage within a single season was immense. If you come back for a second season, Greig adds, "you're never really going to be seen as eligible"

Courtship usually takes one year in Austen's novels, says historian Amanda Vickery, author of The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England. "put female reputation at risk"

For debuting in society, there was not yet a formal age, but women were generally in their late teens, Greig says; men were a little older, and usually spent a few years on a "grand tour" of Europe, essentially an extended gap year, where they "pretended to look at art" she says, and were known to visit brothels.

Will a single woman with a man caught alone be ruined?

If anybody had seen an unmarried woman canoeing in a dark garden with a man, as Daphne did, she would have been in deep trouble.

"No virtuous young lady could be alone with a man to whom she was not related. Not only should she be pure, she should be seen to be pure," Vickery says. "Chastity, modesty and obedience were the pre-eminent female virtues. Her sexual virtue had to appear unimpeachable or she would be ruined on the marriage market."

Vickery cites James Fordyce, a minister who wrote a popular book called Sermons for Young Women: "Remember how tender a thing a woman's reputation is; how hard to preserve, and when lost, how impossible to recover."

All this policing was for money rather than morals, Greig says. "The point of marriage in the aristocracy is to produce a legitimate heir, so if there is any question abut the legitimacy of the person who is inheriting that estate, it throws the whole idea into disarray."

A chaperone — an older family member or even a friend of the same age — will accompany young people in public. The point was to protect their integrity and restrict their interaction with members of the opposite sex, unless they fell for an immoral actor or footman or anyone else, Greig says. "There was a sense in which these women were considered property assets to be managed."

So, is there anything Daphne knows about birds and bees?

A little perhaps.

"There would have been nothing in the way of formal sex education — mothers might have given some premarital counsel to daughters, but although it almost certainly wasn't actually 'close your eyes and think of England', it may not have been much more illuminating," says Lesley A Hall, a gender and sexuality historian.

"Married sisters or friends might have provided some information. Also, it's clear that servants' gossip also conveyed knowledge, though not necessarily helpful or accurate knowledge, to children."

Feminists participating in the social purity movement started to contend "that it was wrong to equate ignorance with innocence and that girls should have some knowledge of sexual matters" until late in the 19th century. Says Hall.

She doesn't have married sisters to look to for help because Daphne is the oldest of the Bridgerton daughters. Indeed, Eloise (Claudia Jessie), her younger sister, is baffled to learn of an unmarried maid who has become pregnant. The only advice comes from her mother, who uses abstract metaphors about rain to tell her what to expect on her wedding night.

Fashionable visual pornography, such as that by Thomas Rowlandson, says Vickery, may have glimpsed a woman of Daphne's size, or seen animals mating on the farm. But it would have seriously restricted her visibility.

Whatever the case, for a genteel young woman hoping to marry well, sexual naivete, or at least the appearance of it, would have been crucial, Vickery says.

"Doubtless her mother would have tutored her on the importance of submitting to her husband and producing an heir and a spare. But she would still be expected to be an innocent virgin on her wedding night. Any knowledge she might have had would be carefully concealed."

"There was great concern if they read too many novels that might give them lots of sexual ideas."It was a great concern if they read too many novels that might give them lots of sexual ideas.

What about her period, though?

Women knew the value of their menstrual cycle, but not how fertility was influenced by it, Vickery says.

Vickery says, "I have come across women's diaries that note their monthly periods as 'the arrival of the flowers' and 'the French lady's visit'," Women also understood that "if they bled they had not conceived"

But the medical profession "little understood ovulation and there was disagreement about when a woman might be most fertile. Everyone, however, agreed that male "seed" was crucial to conception." It was often wrongly assumed that conception was vital to female orgasm.

Had the maid Daphne learned more than her mistress?

Daphne finally turns to her maid, Rose (Molly McGlynn), to speak directly about the realities of life, irritated by her lack of knowledge about sex. It is not a stretch to imagine that Rose would have learned more about intimate matters.

Premarital sex was a popular and accepted part of advanced courtship among the labouring poor,"Amongst the labouring poor, premarital sex was a common and accepted part of advanced courtship," "A high proportion of ordinary brides were pregnant on their wedding day. The servants would likely be much more experienced."

Maybe they didn't have much say in the matter. Domestic servants were regularly treated by their male bosses as prey, Greig says.

The Georgians were not notorious for being a little decadent?

Yes, but as we see in Bridgerton, the lustful behavior of the ballroom is carefully omitted, Greig says. The Georgian age (1714 to 1837), which includes the Regency era (1811 to 1820), is considered by many historians as the true "sexual revolution" in the Western world, not the 1960s. British culture became much more modern over the course of a century, and church rules governing sexuality were left by the wayside.

We know that, in general, Regency society is a very bawdy society,"We know that Regency society is a very bawdy society, generally," "Extramarital sex is no longer illegal, most adult consensual sex is within the law, there's a very open culture of prostitution in London. We get celebrity courtesans and mistresses."

This permissiveness began at the top: from 1811 to 1820, the Prince Regent (later King George IV), who served as a proxy for his father, the mentally ill King George III, had several mistresses, a secret illicit marriage, and many rumoured illegitimate children.

Would a man like Simon not have wanted children?

Yeah. Yes. One of the most implausible things about Bridgerton may be Simon's adamant insistence on not being a father. "Noble men married to secure the dynasty. A peer determined not to have children would be absurd," says Vickery. "Virility and potency were seen as archetypal male positive attributes." At the same time, "Women were under considerable pressure to produce heirs" and were generally blamed when they did not. "Infertility was a source of shame," she says. However, it is probable that withdrawal will be Simon's chosen birth control form.

When it came to sex, was there a double standard?

This element of Regency culture is well captured by Bridgerton. "Genteel girls were expected to be innocent virgins on their wedding day to men of the world who had already practiced on married women abroad, servant girls, the odd actress and prostitutes," Vickery says. "Men's diaries are extraordinarily casual in reporting sex with servants. After marriage, a man had a right to demand sexual servicing. There was no such crime as marital rape. Women were everywhere told to turn a blind eye to men's peccadilloes and indiscretions." Until 1922, a man could divorce his wife alone for adultery, but for women the same was not valid.

This double standard meant that men were capable of despising and devaluing any women who were prepared to sleep with them outside marriage, Vickery explains, referencing the colorful admonition of the elder Lord Sandwich: "He that doth get a wench with child and marries her afterwards is as if a man should shit in his hat and then clap it on his head."

It was not unheard of for a married woman to have an affair as long as she kept it secret, Greig says, until she had produced an heir. "If it makes the scandal sheet, it's a problem."