David Ramirez stabbed his girlfriend Mary Ann Gortarez and daughter Candie

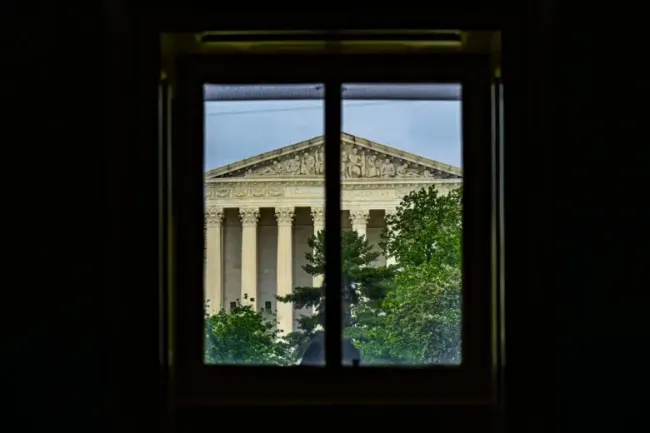

The Supreme Court puts limits on what inmates can do if they had bad legal help.

The justices decided, 6 to 3, that federal courts can't hold hearings to look at evidence in cases where state prisoners say their lawyers didn't help them enough.

On Monday, the Supreme Court ruled against two Arizona death row inmates and made it much harder for prisoners to challenge their convictions in federal court. They did this by saying that their lawyers had not done a good job in state court.

The 6–3 vote was divided by different ideas. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the majority, said that a federal court considering a habeas corpus petition "may not hold an evidentiary hearing or otherwise consider evidence beyond the state court record based on ineffective assistance of state post-conviction counsel."

He made his decision based on language in a federal law from 1996 that limits habeas corpus petitions, the importance of finality to the judicial system, and the fact that each state is independent.

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote that the majority "almost completely overturns two recent precedents that recognized a key exception to the general rule that federal courts can't look at claims on habeas review that weren't brought up in state court."

She also said, "Two men whose trial lawyers didn't do even the bare minimum of what the Constitution requires could be put to death because things they couldn't control kept them from exercising their constitutional right to a lawyer."

David Ramirez, one of the men, killed his girlfriend Mary Ann Gortarez and her 15-year-old daughter Candie with a knife. In state court, Mr. Ramirez was found guilty and given a death sentence. Later, in federal court, his lawyers said that his trial lawyer didn't look into or present evidence about his intellectual and developmental disabilities that might have made the jury more lenient.

Barry Lee Jones, the other person in jail, was found guilty of killing Rachel Gray, his girlfriend's 4-year-old daughter. Justice Sotomayor wrote, "Jones's trial lawyer didn't do even a quick investigation, so he didn't find easily accessible medical evidence that could have shown Rachel got hurt when she wasn't in Jones's care."

In two decisions made about a decade ago, Martinez v. Ryan in 2012 and Trevino v. Thaler in 2013, the Supreme Court let some federal challenges to state convictions go forward when lawyers in the state courts had been ineffective at trial and in post-conviction challenges.

On Monday, Justice Thomas wrote that those decisions did not take into account long hearings in federal court to look at new evidence.

"The sprawling hearing of evidence in Jones is very moving," he wrote as an example. "The district court ordered a seven-day hearing that included testimony from at least 10 witnesses, including the defense trial counsel, the defense post-conviction counsel, the lead investigating detective, three forensic pathologists, an emergency medicine and trauma specialist, a biomechanics and functional human anatomy expert, and a crime scene and bloodstain pattern analyst. This was ostensibly to assess cause and prejudice under Martinez."

"This whole new round of arguing about Jones' guilt," added Justice Thomas, "is obviously not what Martinez had in mind."

Justice Sotomayor said that Mr. Jones needed a hearing because his lawyers had not done a good job. "The district court hearing was so broad because the breakdown of the adversarial system in Jones's case was so egregious," she wrote.

Justice Sotomayor said that because of the Supreme Court's decision, "many people who were wrongfully convicted in violation of the Sixth Amendment will be locked up or even put to death without a real chance to defend their right to counsel."

Justice Thomas's opinion was shared by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Stephen G. Breyer and Elena Kagan also disagreed with Justice Sotomayor.

Robert M. Loeb, who fought for Mr. Ramirez and Mr. Jones in front of the Supreme Court, was unhappy with the decision.

He said in a statement, "The court's decision means that the fundamental constitutional right to trial counsel has no effective way to be enforced in this case." "The decision misinterprets the federal law, leads to unworkable outcomes that Congress never thought of, and is an attack on the basic fairness of the criminal justice system."

The attorney general of Arizona, Mark Brnovich, was happy with the decision in Shinn v. Ramirez, No. 20-1009.

In a statement, he said, "The wheels of justice take time to turn, but they shouldn't be stuck for decades." "I applaud the Supreme Court's decision because it will help society refocus on getting justice for victims instead of wasting time with endless delays that let killers get away with their horrible crimes."